|

Contrary to popular opinion there never was a country called Greece or Hellas until the Revolution of 1821. When rebellion against the Ottoman Empire gave birth to Hellas, Hellenic-speaking people had a national homeland for the first time in history.

|

|

In 1821 the land that was known as Greece is controlled by the Turks, except for the Ionian islands which has been occupied by the Venetians, then the French and

in 1815 by the

British.

The rebellion of the Greeks actually

begins in Moldavia when an army of 4500 Hellenes led by General Alexander Ypsilantis, a Phanariot from the so-named district of Istanbul, a member of the Philike Hetairia (Friendly Society), invades hoping to encourage the local Romanian peasants to throw off the yoke of the Turks. Instead they attack their wealthy countrymen and the Greeks have to escape. When the revolution breaks out in the Peloponessos, the Sultan in Istanbul hangs the Patriarch Grigorios V for failing to keep the Greek Christians in

line

which they considered his duty for the vast privileges they allowed him. The Phanariot Greeks fall in line behind the new patriarch and condemn the revolution. But in the Peloponessos the rebellion is making progress and combined with Ali Pasha's rebellion in Ipirus the Turks have their hands full. On March 25th 1821 Bishop Germanos of Patras raises the flag of revolution at the monastery of Agia Lavra near Kalavrita and the battle cry of "Freedom or Death" becomes the motto of the revolution. But historian David Brewer in his Greece, The Hidden Centuries: Turkish Rule from the Fall of Constantinople to Greek Independence disagrees, stating that the story of the flag raising at Agia Lavra was apparently an invention by Francois Pouqueville, a prominent

architect of the Philhellenism movement throughout Europe, who contributed to the liberation of the Greeks, and to the rebirth of the Greek Nation. In 1821 the land that was known as Greece is controlled by the Turks, except for the Ionian islands which has been occupied by the Venetians, then the French and

in 1815 by the

British.

The rebellion of the Greeks actually

begins in Moldavia when an army of 4500 Hellenes led by General Alexander Ypsilantis, a Phanariot from the so-named district of Istanbul, a member of the Philike Hetairia (Friendly Society), invades hoping to encourage the local Romanian peasants to throw off the yoke of the Turks. Instead they attack their wealthy countrymen and the Greeks have to escape. When the revolution breaks out in the Peloponessos, the Sultan in Istanbul hangs the Patriarch Grigorios V for failing to keep the Greek Christians in

line

which they considered his duty for the vast privileges they allowed him. The Phanariot Greeks fall in line behind the new patriarch and condemn the revolution. But in the Peloponessos the rebellion is making progress and combined with Ali Pasha's rebellion in Ipirus the Turks have their hands full. On March 25th 1821 Bishop Germanos of Patras raises the flag of revolution at the monastery of Agia Lavra near Kalavrita and the battle cry of "Freedom or Death" becomes the motto of the revolution. But historian David Brewer in his Greece, The Hidden Centuries: Turkish Rule from the Fall of Constantinople to Greek Independence disagrees, stating that the story of the flag raising at Agia Lavra was apparently an invention by Francois Pouqueville, a prominent

architect of the Philhellenism movement throughout Europe, who contributed to the liberation of the Greeks, and to the rebirth of the Greek Nation.

|

|

Nevertheless, fighting begins to break out all over with massacres committed by both the Greeks and the Turks. On the island of Chios 25,000 Greeks are killed while in the Peloponessos the Greeks kill 15,000 of the 40,000 Turks living there. It would be unfair to over-look Ali Pasha and the fact that the insurrection of 1821 was actually something

of an Albanian affair and that the Chios massacre was a consequence of this. The Chiotes had enormous privileges under the Ottomans even to the point of dominating the Ottoman admiralty. It was the role of the Chios 'navy' in the revolt that was seen as an act of treason by the Turks, though in Brewer's book the Chios navy was less than eager to join the fray and the cause of the Turkish invasion was the fact that the Samos navy has landed on the island and occupied the citadel. Nevertheless, fighting begins to break out all over with massacres committed by both the Greeks and the Turks. On the island of Chios 25,000 Greeks are killed while in the Peloponessos the Greeks kill 15,000 of the 40,000 Turks living there. It would be unfair to over-look Ali Pasha and the fact that the insurrection of 1821 was actually something

of an Albanian affair and that the Chios massacre was a consequence of this. The Chiotes had enormous privileges under the Ottomans even to the point of dominating the Ottoman admiralty. It was the role of the Chios 'navy' in the revolt that was seen as an act of treason by the Turks, though in Brewer's book the Chios navy was less than eager to join the fray and the cause of the Turkish invasion was the fact that the Samos navy has landed on the island and occupied the citadel.

On March 13th 1821, twelve days before the official beginning of the War of Independence, the first 'revolutionary flag' was actually raised on the island of Spetses by Laskarina Bouboulina (though there were several revolutionary flags which could lay claim to being the

first, including Hydra). Twice widowed with 7 children but extremely rich she owned several ships. On April 3rd

Spetses revolted,

followed by the islands of Hydra and Psara with a total of over 300 ships between them. Bouboulina and her fleet of 8 ships sailed to Nafplion and took part in the siege of the impregnable fortress there. Her later attack on Monemvasia managed to capture that fortress. She took part in the blockade of Pylos and brought supplies to the revolutionaries by sea. Bouboulina became a national hero, one of the first women to play a major role in a

revolution. Without her and her ships the Greeks might not have gained their independence. What is less well known is that she was Albanian.

|

|

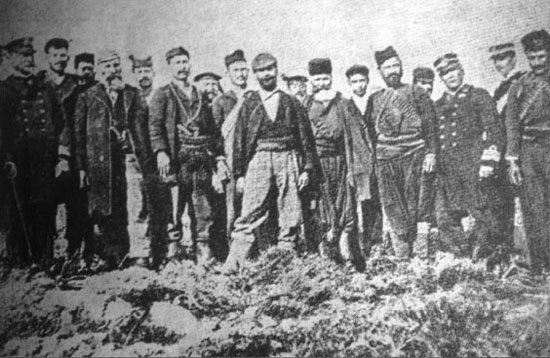

The Greeks, led by local heroes like Theodoros Kolokotronis from the Mani, capture the Peloponessos and form a provisional government, electing the Phanariot Alexandros Mavrokordatos president. On April 26th the Greeks attack Athens and the Turks of the city are forced to flee to the Acropolis. They are rescued in August by Turkish troops but finally surrender in June of 1822. By mid July, about half had been massacred, others died of disease, and over the next months the rest (550) were evacuated by foreign

diplomats. In the meantime the Greeks in the Peloponessos, (or the Morea as it was

called), are fighting amongst themselves. In European

cities intellectuals and poets like Lord Byron embrace the Greek cause and sway public opinion. The Greek struggle is interpreted by many Europeans simplistically and romantically as a battle between the ideals of the ancient Greeks against the ruthless Turks who had been occupying and suppressing the descendents of Pericles, Socrates and Plato. Many, including

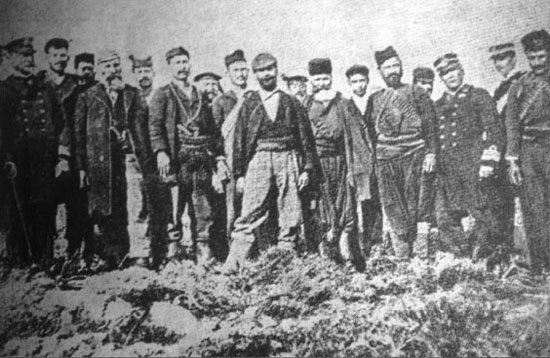

Lord Byron, volunteer to fight and become leaders and

heroes of the revolution, known as the Philhellenes (friends of the Greeks). Some sing the praises of the modern Greeks but many are completely disillusioned by the pettiness and greed of the Greek klefth leaders who seem to just want glory and riches. Though some of these warlords are elevated to the role of saviors and heroes in the national mythology, the reality is that many of them were just pirates and thieves looking out for their own self-interest. On the other hand the motives of the Europeans

is just as suspect and the plan for Greece was actually to be a sort of colony of Great Britain (or several colonies) since the last thing in the world they wanted was every national group on the continent being inspired by events in Greece and trying to start their own country too. But as history so often shows us, once you get the engine of revolution started you can't really control where it takes you. The Greeks, led by local heroes like Theodoros Kolokotronis from the Mani, capture the Peloponessos and form a provisional government, electing the Phanariot Alexandros Mavrokordatos president. On April 26th the Greeks attack Athens and the Turks of the city are forced to flee to the Acropolis. They are rescued in August by Turkish troops but finally surrender in June of 1822. By mid July, about half had been massacred, others died of disease, and over the next months the rest (550) were evacuated by foreign

diplomats. In the meantime the Greeks in the Peloponessos, (or the Morea as it was

called), are fighting amongst themselves. In European

cities intellectuals and poets like Lord Byron embrace the Greek cause and sway public opinion. The Greek struggle is interpreted by many Europeans simplistically and romantically as a battle between the ideals of the ancient Greeks against the ruthless Turks who had been occupying and suppressing the descendents of Pericles, Socrates and Plato. Many, including

Lord Byron, volunteer to fight and become leaders and

heroes of the revolution, known as the Philhellenes (friends of the Greeks). Some sing the praises of the modern Greeks but many are completely disillusioned by the pettiness and greed of the Greek klefth leaders who seem to just want glory and riches. Though some of these warlords are elevated to the role of saviors and heroes in the national mythology, the reality is that many of them were just pirates and thieves looking out for their own self-interest. On the other hand the motives of the Europeans

is just as suspect and the plan for Greece was actually to be a sort of colony of Great Britain (or several colonies) since the last thing in the world they wanted was every national group on the continent being inspired by events in Greece and trying to start their own country too. But as history so often shows us, once you get the engine of revolution started you can't really control where it takes you.

In 1823 Lord Byron arrives in Missolonghi,

to take part in the resistance there, but dies three months later, not as romantically as he would have liked, but by disease. In 1826 the Peloponessos is back in Turkish hands and Athens is one of only a few cities controlled by the Greeks. When the Turkish army returns, a major battle takes place and on June 5th the Acropolis is surrendered. Among the fifteen hundred Greek dead are 22 of the 26 Philhellenes. By 1827 the Turks have all of Greece with the exception of Nafplion and a few islands.

|

|

But the Greeks are rescued by their own history as support

for them in their struggle grows. The Treaty of London, backed by Britain, Russia and France. declares that the three great powers can intervene 'peacefully' to secure

the autonomy of the Hellenes. In October of that year the British, French and

Russians show the power of peaceful intervention when they destroy the Turkish-Egyptian

fleet in the bay of Navarino (Pylos) in what may have been the world's biggest

and most fatal 'misunderstanding'. Whether by accident or not, when an Egyptian

ship fires on a small boat filled with British sailors, all hell breaks

loose and when the smoke clears the entire Turkish-Egyptian fleet is at the

bottom of the bay, (where they can still be seen). It is the most one-sided

battle in the history of naval warfare.

With the destruction of the Egyptian-Turkish fleet the Hellenes have a clear

path to nationhood except for the usual fighting amongst themselves. But the Greeks are rescued by their own history as support

for them in their struggle grows. The Treaty of London, backed by Britain, Russia and France. declares that the three great powers can intervene 'peacefully' to secure

the autonomy of the Hellenes. In October of that year the British, French and

Russians show the power of peaceful intervention when they destroy the Turkish-Egyptian

fleet in the bay of Navarino (Pylos) in what may have been the world's biggest

and most fatal 'misunderstanding'. Whether by accident or not, when an Egyptian

ship fires on a small boat filled with British sailors, all hell breaks

loose and when the smoke clears the entire Turkish-Egyptian fleet is at the

bottom of the bay, (where they can still be seen). It is the most one-sided

battle in the history of naval warfare.

With the destruction of the Egyptian-Turkish fleet the Hellenes have a clear

path to nationhood except for the usual fighting amongst themselves.

|

|

In an interesting anecdote about the war, when the Turkish garrison of Athens was using the

acropolis as a fortress they came under siege by the Greek revolutionary

army. After a few days, the Turks were short of ammunition and the Greeks

noticed from far away that they were taking down the marble columns and

extracting the lead wedge that holds the "slices" of the columns together. (If you have noticed some

fallen columns like at the temple of Olympian Zeus, you will see in the

center of the slices, a hollow part. This was filled with lead by the

ancient architects and made the columns stronger, and able to resist the frequent

small earthquakes which happen all the time around Attica.) The Greeks sent

an envoy to the Turks and asked them how much lead they would obtain by

taking down all the columns of the Parthenon. They agreed on the quantity of

the lead, and the Greeks sent it to the Turks with the agreement that they

would leave the remaining temple of the Parthenon intact. This shows how

much the Greek warriors who could hardly read or write, appreciated

their ancient Greek heritage, though it didn't stop them

from taking the entire ancient library of Kaisariani Monastery

onto the Acropolis and tearing up the books to use the paper for

cartridges!

|

|

In 1828 Count Ioannis Capodistrias of

Corfu is elected the first governor of Greece by the

assembly of Troezene as the Turkish-Egyptian army leave the Peloponessos once

and for all. The Greeks draw up a constitution as a republic and

on March 31st 1833 the Turkish troops who have been occupying the

Acropolis leave. Four years after

being elected President, Kapodistrias is assassinated in the new capital city of Nafplion

supposedly by members of a Mani clan, the Mavromichalis family, who were at odds with his belief in a

strong central government, (though some people believe he was killed by the British who blamed the Mavromichalis and thus eliminated two problems). A year later the 17 year old Otto (Othon), son of Ludwig of Bavaria, is declared

King of the Hellenes by the British, Russians and French. He arrives in Nafplion by boat

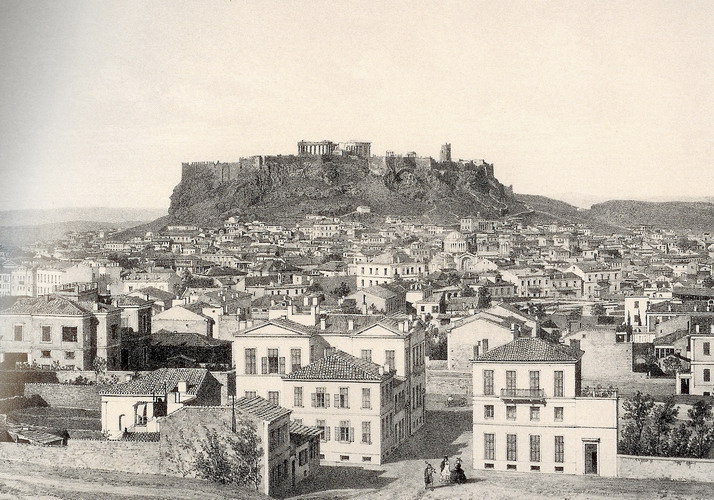

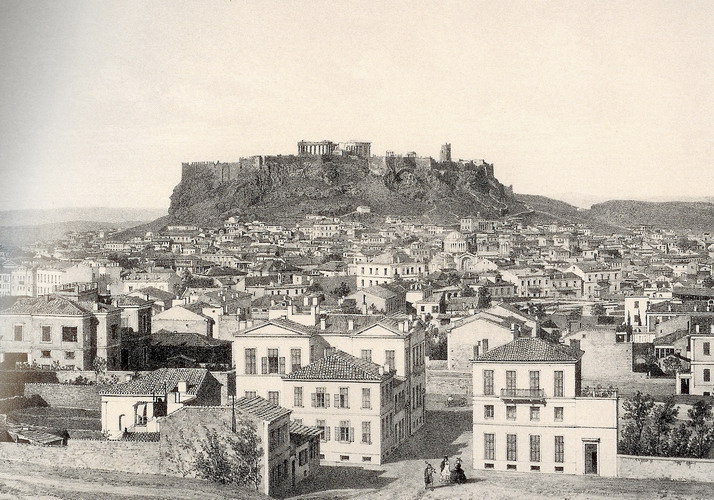

a year later to great fanfare. In 1834 the capital is moved to Athens, which

is now a

town of 10,000 inhabitants. In 1837 the University of Athens opens. King Otto is forced by the military

to accept a constitution in 1843. He is overthrown by the army in 1862

and he and his wife Amalia are exiled and

replaced in 1863 by the Danish Prince Christian William Ferdinand Adolphus George

of the Holstein-Sonderburg-Gluckbsburg who becomes George I, King of the Hellenes.

In March of 1864 the Ionian islands are ceded to Greece by Great Britain. In 1828 Count Ioannis Capodistrias of

Corfu is elected the first governor of Greece by the

assembly of Troezene as the Turkish-Egyptian army leave the Peloponessos once

and for all. The Greeks draw up a constitution as a republic and

on March 31st 1833 the Turkish troops who have been occupying the

Acropolis leave. Four years after

being elected President, Kapodistrias is assassinated in the new capital city of Nafplion

supposedly by members of a Mani clan, the Mavromichalis family, who were at odds with his belief in a

strong central government, (though some people believe he was killed by the British who blamed the Mavromichalis and thus eliminated two problems). A year later the 17 year old Otto (Othon), son of Ludwig of Bavaria, is declared

King of the Hellenes by the British, Russians and French. He arrives in Nafplion by boat

a year later to great fanfare. In 1834 the capital is moved to Athens, which

is now a

town of 10,000 inhabitants. In 1837 the University of Athens opens. King Otto is forced by the military

to accept a constitution in 1843. He is overthrown by the army in 1862

and he and his wife Amalia are exiled and

replaced in 1863 by the Danish Prince Christian William Ferdinand Adolphus George

of the Holstein-Sonderburg-Gluckbsburg who becomes George I, King of the Hellenes.

In March of 1864 the Ionian islands are ceded to Greece by Great Britain.

|

|

In

1878 Great Britain takes over the administration of Cyprus from

the Ottoman government. Two

years later revolution breaks out in the still Turkish occupied island of Crete. In

1881 Thessaly and the Arta region of Epirus are ceded to Greece by the Ottoman

empire. From the mid-1880's to 90's Harilaos Trikoupis and Theodoror Deliyannis

alternate power, in what is the beginning of a two-party system.

Trikoupis focuses on domestic issues and during his rule roads are

built, tracks are laid, the metro is built and even the Corinth

Canal which had been started by Nero in 67 AD is completed

in 1893. Deliyannis on the other hand is a believer in the Megalo Idea, that

Greece will one day rule a new Hellenic empire along the lines of

the Byzantine.

|

|

During

the mid to late eighteen-hundreds, architects came from Europe to build a new Athens of neo-classical buildings

with the help of local architects and benefactors of the Hellenic diaspora society.

In 1842 a wealthy Greek from Trieste named Antonis Dimitriou had built

a house for himself in the center of Athens which in 1874 becomes

the Hotel

Grande Bretagne. It becomes the hotel of choice for kings, queens

and dignitaries and the scene of many important moments modern

Greek history. Some other examples include the Evangelismos Hospital built by Andrea Syngros from

the island of Chios, the Zappion which was a gift of the Zappas brothers from

Northern Epirus, the Athens Polytechnic which was built by Nicholas Stournaras

from Metsovo and the King's

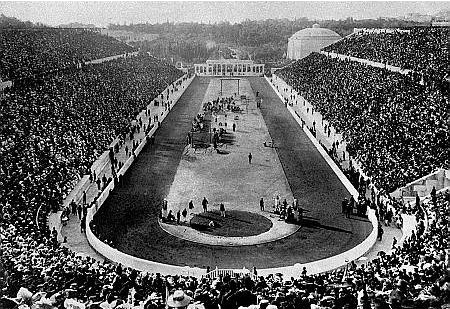

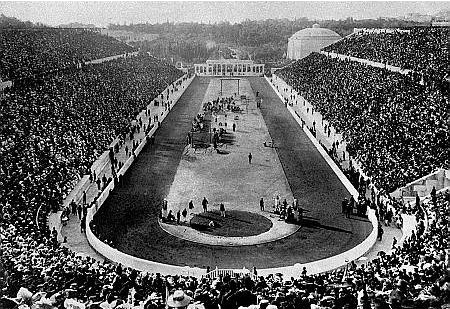

Palace (now the Parliament building in Syntagma). Perhaps the largest and most important gift is the reconstruction

of the ancient marble Panathenaic Stadium by George Averof, an Alexandrian businessman

from Metsovo for the Olympic games of 1896. By then the population of the city

is around 130,000 and the Olympics are a sort of coming-out party for the

new capital city of Europe's newest nation. During

the mid to late eighteen-hundreds, architects came from Europe to build a new Athens of neo-classical buildings

with the help of local architects and benefactors of the Hellenic diaspora society.

In 1842 a wealthy Greek from Trieste named Antonis Dimitriou had built

a house for himself in the center of Athens which in 1874 becomes

the Hotel

Grande Bretagne. It becomes the hotel of choice for kings, queens

and dignitaries and the scene of many important moments modern

Greek history. Some other examples include the Evangelismos Hospital built by Andrea Syngros from

the island of Chios, the Zappion which was a gift of the Zappas brothers from

Northern Epirus, the Athens Polytechnic which was built by Nicholas Stournaras

from Metsovo and the King's

Palace (now the Parliament building in Syntagma). Perhaps the largest and most important gift is the reconstruction

of the ancient marble Panathenaic Stadium by George Averof, an Alexandrian businessman

from Metsovo for the Olympic games of 1896. By then the population of the city

is around 130,000 and the Olympics are a sort of coming-out party for the

new capital city of Europe's newest nation.

|

|

But the Olympics of 1896 which are credited as the first of the modern Olympics actually weren't. In 1833 Panagiotis Soutsos wrote about the revival of the Olympic Games in

his poetry 'Dialogue of the Dead' and in 1850 Dr William Penny Brookes founded annual games in Much Wenlock,

Shropshire, UK. In 1856 Evangelis Zappas wrote to King Otto of Greece offering to fund the

revival of the Olympic Games. The first modern international Olympic Games held in Athens at Platia Kotzia, then called Ludouvikou or Ludvig Square, in 1859, sponsored by Evangelis Zappas. The 'Zappas Games'

welcomed participants from the Ottoman Empire as well as Greece, making the Games

international. In 1860 Dr William Penny Brookes founded the Wenlock Olympian

Society. Brookes was clearly inspired by the first modern Olympic Games

since he incorporated some of the events into the Wenlock Olympian Games. Petros Velissariou was the first person to be listed on the honorary roll as the first Olympic victor for his performance in the 1859 Zappas Games. In 1863 Baron Pierre de Coubertin was born. Why is this mentioned? Coubertin is hailed as the founder of the modern Olympics and the Olympic Committee and yet when he was born both had already been in existence. In 1870, when Coubertin was just seven years old, the

first modern Olympics to be held in a stadium took place in the ancient Panathenaic stadium of Athens which had been rebuilt by Evangelis Zappas. In 1875 the third games were held at the stadium and in 1889 another series of games was held in another location. It was not until 1892 that both Dr William Penny Brookes and Baron Pierre de Coubertin publicly

proposed the revival of the Olympic Games for the first time with Brooke's proposal coming first. In 1894 Baron Pierre de Coubertin founded the International Olympic

Committee. But the Olympics of 1896 which are credited as the first of the modern Olympics actually weren't. In 1833 Panagiotis Soutsos wrote about the revival of the Olympic Games in

his poetry 'Dialogue of the Dead' and in 1850 Dr William Penny Brookes founded annual games in Much Wenlock,

Shropshire, UK. In 1856 Evangelis Zappas wrote to King Otto of Greece offering to fund the

revival of the Olympic Games. The first modern international Olympic Games held in Athens at Platia Kotzia, then called Ludouvikou or Ludvig Square, in 1859, sponsored by Evangelis Zappas. The 'Zappas Games'

welcomed participants from the Ottoman Empire as well as Greece, making the Games

international. In 1860 Dr William Penny Brookes founded the Wenlock Olympian

Society. Brookes was clearly inspired by the first modern Olympic Games

since he incorporated some of the events into the Wenlock Olympian Games. Petros Velissariou was the first person to be listed on the honorary roll as the first Olympic victor for his performance in the 1859 Zappas Games. In 1863 Baron Pierre de Coubertin was born. Why is this mentioned? Coubertin is hailed as the founder of the modern Olympics and the Olympic Committee and yet when he was born both had already been in existence. In 1870, when Coubertin was just seven years old, the

first modern Olympics to be held in a stadium took place in the ancient Panathenaic stadium of Athens which had been rebuilt by Evangelis Zappas. In 1875 the third games were held at the stadium and in 1889 another series of games was held in another location. It was not until 1892 that both Dr William Penny Brookes and Baron Pierre de Coubertin publicly

proposed the revival of the Olympic Games for the first time with Brooke's proposal coming first. In 1894 Baron Pierre de Coubertin founded the International Olympic

Committee.

|

|

In 1896 the Fourth modern international Olympic Games and the first IOC Olympic

Games were held at the Panathenian Stadium, in Athens, the stadium again having been refurbished by Zappas and fellow philanthropist George Averoff. The Zappeion building was the first indoor Olympic arena. So while you could argue that Coubertin was the founder of the International Olympic Committee, this line of reasoning falters when it comes to the modern Olympics which were inspired by Panayiotis Soutsos and paid for by Evangels Zappas approximately 1,460 years after

the Ancient Olympic Games had been banned by the

first Christian Roman Emperor Theodosius I. (For more see www.zappas.org where you can join the campaign to formally recognise Panagiotis Soutsos and Evangelis Zappas as founders of the

modern Olympic Games and Dr William Penny Brookes as a founder of the modern

Olympic Movement.) In 1896 the Fourth modern international Olympic Games and the first IOC Olympic

Games were held at the Panathenian Stadium, in Athens, the stadium again having been refurbished by Zappas and fellow philanthropist George Averoff. The Zappeion building was the first indoor Olympic arena. So while you could argue that Coubertin was the founder of the International Olympic Committee, this line of reasoning falters when it comes to the modern Olympics which were inspired by Panayiotis Soutsos and paid for by Evangels Zappas approximately 1,460 years after

the Ancient Olympic Games had been banned by the

first Christian Roman Emperor Theodosius I. (For more see www.zappas.org where you can join the campaign to formally recognise Panagiotis Soutsos and Evangelis Zappas as founders of the

modern Olympic Games and Dr William Penny Brookes as a founder of the modern

Olympic Movement.)

|

|

The same year that the Olympics

are held another rebellion breaks out in Crete. Greece, under Deliyannis backs

the island's liberation and declares war on Turkey.

In three weeks the Greek army is defeated but Crete is put under international administration. In 1898 Crete is granted autonomy and Prince

George, the 2nd son of the King is appointed governor. The same year that the Olympics

are held another rebellion breaks out in Crete. Greece, under Deliyannis backs

the island's liberation and declares war on Turkey.

In three weeks the Greek army is defeated but Crete is put under international administration. In 1898 Crete is granted autonomy and Prince

George, the 2nd son of the King is appointed governor.

In Turkey events are taking place that will

change the face of Asia Minor and Greece too. Sultan Abdul Hamit of

the Ottoman Empire applies a policy of genocide to the Armenians. In August

and September 1894, Armenians are slain in Sassun. In October 1895

the first organised genocide takes place in Constantinople and Trebizond and in November and

December 1895 the Ottoman authorities organize a great massacre throughout the country.

In June 1896, the massacre of Van takes place. After the capture by the

Armenians of the Ottoman Bank, another massacre takes place in

Constantinople. The total number of victims is 300.000 Armenian men, women and

children.

In 1905 Eleftherios

Venizelos, the president of the Cretan assembly announces the Union

(enosis) with Greece. Though this union is not recognized until

1913, Venizelos comes to Athens where he becomes one of the most

important political players of 20th century Greece.

|

|

Nevertheless, fighting begins to break out all over with massacres committed by both the Greeks and the Turks. On the island of Chios 25,000 Greeks are killed while in the Peloponessos the Greeks kill 15,000 of the 40,000 Turks living there. It would be unfair to over-look Ali Pasha and the fact that the insurrection of 1821 was actually something

of an Albanian affair and that the Chios massacre was a consequence of this. The Chiotes had enormous privileges under the Ottomans even to the point of dominating the Ottoman admiralty. It was the role of the Chios 'navy' in the revolt that was seen as an act of treason by the Turks, though in Brewer's book the Chios navy was less than eager to join the fray and the cause of the Turkish invasion was the fact that the Samos navy has landed on the island and occupied the citadel.

Nevertheless, fighting begins to break out all over with massacres committed by both the Greeks and the Turks. On the island of Chios 25,000 Greeks are killed while in the Peloponessos the Greeks kill 15,000 of the 40,000 Turks living there. It would be unfair to over-look Ali Pasha and the fact that the insurrection of 1821 was actually something

of an Albanian affair and that the Chios massacre was a consequence of this. The Chiotes had enormous privileges under the Ottomans even to the point of dominating the Ottoman admiralty. It was the role of the Chios 'navy' in the revolt that was seen as an act of treason by the Turks, though in Brewer's book the Chios navy was less than eager to join the fray and the cause of the Turkish invasion was the fact that the Samos navy has landed on the island and occupied the citadel.

But the Olympics of 1896 which are credited as the first of the modern Olympics actually weren't. In 1833 Panagiotis Soutsos wrote about the revival of the Olympic Games in

his poetry 'Dialogue of the Dead' and in 1850 Dr William Penny Brookes founded annual games in Much Wenlock,

Shropshire, UK. In 1856 Evangelis Zappas wrote to King Otto of Greece offering to fund the

revival of the Olympic Games. The first modern international Olympic Games held in Athens at Platia Kotzia, then called Ludouvikou or Ludvig Square, in 1859, sponsored by Evangelis Zappas. The 'Zappas Games'

welcomed participants from the Ottoman Empire as well as Greece, making the Games

international. In 1860 Dr William Penny Brookes founded the Wenlock Olympian

Society. Brookes was clearly inspired by the first modern Olympic Games

since he incorporated some of the events into the Wenlock Olympian Games. Petros Velissariou was the first person to be listed on the honorary roll as the first Olympic victor for his performance in the 1859 Zappas Games. In 1863 Baron Pierre de Coubertin was born. Why is this mentioned? Coubertin is hailed as the founder of the modern Olympics and the Olympic Committee and yet when he was born both had already been in existence. In 1870, when Coubertin was just seven years old, the

first modern Olympics to be held in a stadium took place in the ancient Panathenaic stadium of Athens which had been rebuilt by Evangelis Zappas. In 1875 the third games were held at the stadium and in 1889 another series of games was held in another location. It was not until 1892 that both Dr William Penny Brookes and Baron Pierre de Coubertin publicly

proposed the revival of the Olympic Games for the first time with Brooke's proposal coming first. In 1894 Baron Pierre de Coubertin founded the International Olympic

Committee.

But the Olympics of 1896 which are credited as the first of the modern Olympics actually weren't. In 1833 Panagiotis Soutsos wrote about the revival of the Olympic Games in

his poetry 'Dialogue of the Dead' and in 1850 Dr William Penny Brookes founded annual games in Much Wenlock,

Shropshire, UK. In 1856 Evangelis Zappas wrote to King Otto of Greece offering to fund the

revival of the Olympic Games. The first modern international Olympic Games held in Athens at Platia Kotzia, then called Ludouvikou or Ludvig Square, in 1859, sponsored by Evangelis Zappas. The 'Zappas Games'

welcomed participants from the Ottoman Empire as well as Greece, making the Games

international. In 1860 Dr William Penny Brookes founded the Wenlock Olympian

Society. Brookes was clearly inspired by the first modern Olympic Games

since he incorporated some of the events into the Wenlock Olympian Games. Petros Velissariou was the first person to be listed on the honorary roll as the first Olympic victor for his performance in the 1859 Zappas Games. In 1863 Baron Pierre de Coubertin was born. Why is this mentioned? Coubertin is hailed as the founder of the modern Olympics and the Olympic Committee and yet when he was born both had already been in existence. In 1870, when Coubertin was just seven years old, the

first modern Olympics to be held in a stadium took place in the ancient Panathenaic stadium of Athens which had been rebuilt by Evangelis Zappas. In 1875 the third games were held at the stadium and in 1889 another series of games was held in another location. It was not until 1892 that both Dr William Penny Brookes and Baron Pierre de Coubertin publicly

proposed the revival of the Olympic Games for the first time with Brooke's proposal coming first. In 1894 Baron Pierre de Coubertin founded the International Olympic

Committee.  In 1896 the Fourth modern international Olympic Games and the first IOC Olympic

Games were held at the Panathenian Stadium, in Athens, the stadium again having been refurbished by Zappas and fellow philanthropist George Averoff. The Zappeion building was the first indoor Olympic arena. So while you could argue that Coubertin was the founder of the International Olympic Committee, this line of reasoning falters when it comes to the modern Olympics which were inspired by Panayiotis Soutsos and paid for by Evangels Zappas approximately 1,460 years after

the Ancient Olympic Games had been banned by the

first Christian Roman Emperor Theodosius I. (For more see

In 1896 the Fourth modern international Olympic Games and the first IOC Olympic

Games were held at the Panathenian Stadium, in Athens, the stadium again having been refurbished by Zappas and fellow philanthropist George Averoff. The Zappeion building was the first indoor Olympic arena. So while you could argue that Coubertin was the founder of the International Olympic Committee, this line of reasoning falters when it comes to the modern Olympics which were inspired by Panayiotis Soutsos and paid for by Evangels Zappas approximately 1,460 years after

the Ancient Olympic Games had been banned by the

first Christian Roman Emperor Theodosius I. (For more see  The same year that the Olympics

are held another rebellion breaks out in Crete. Greece, under Deliyannis backs

the island's liberation and declares war on Turkey.

In three weeks the Greek army is defeated but Crete is put under international administration. In 1898 Crete is granted autonomy and Prince

George, the 2nd son of the King is appointed governor.

The same year that the Olympics

are held another rebellion breaks out in Crete. Greece, under Deliyannis backs

the island's liberation and declares war on Turkey.

In three weeks the Greek army is defeated but Crete is put under international administration. In 1898 Crete is granted autonomy and Prince

George, the 2nd son of the King is appointed governor.